Safety

Although the routes are mostly moderate, they cross a wild and exposed landscape with few or no waymarkers – and seldom on what would be regarded as a path on the mainland. Most of the walks can be very wet underfoot, so waterproof boots are highly recommended. The outline map accompanying each walk is intended to help plan the outing rather than as a navigational aid; the relevant Ordnance Survey should always be taken on the wilder routes. Whilst the Outer Hebrides are warmed by the Gulf Stream coming over the Atlantic and thus have a mild climate, this also leads to very changeable weather. Cliché though it is, you may well experience all four seasons in a day here, so it is advisable to pack wind- and water-proof clothing and adequate warm layers to be able to enjoy these walks whatever the conditions. Some of the routes are suitable for families with children in good conditions, although care should be taken on the coastal walks as many of the cliffs are high and unfenced. The Lews Castle walk at Stornoway and the walk to the Eagle Observatory on Harris are possible with an all-terrain buggy. Other routes – such as the ascents of An Cliseam and Eaval – should be treated as proper hillwalks, requiring appropriate equipment and navigation skills.

Public transport

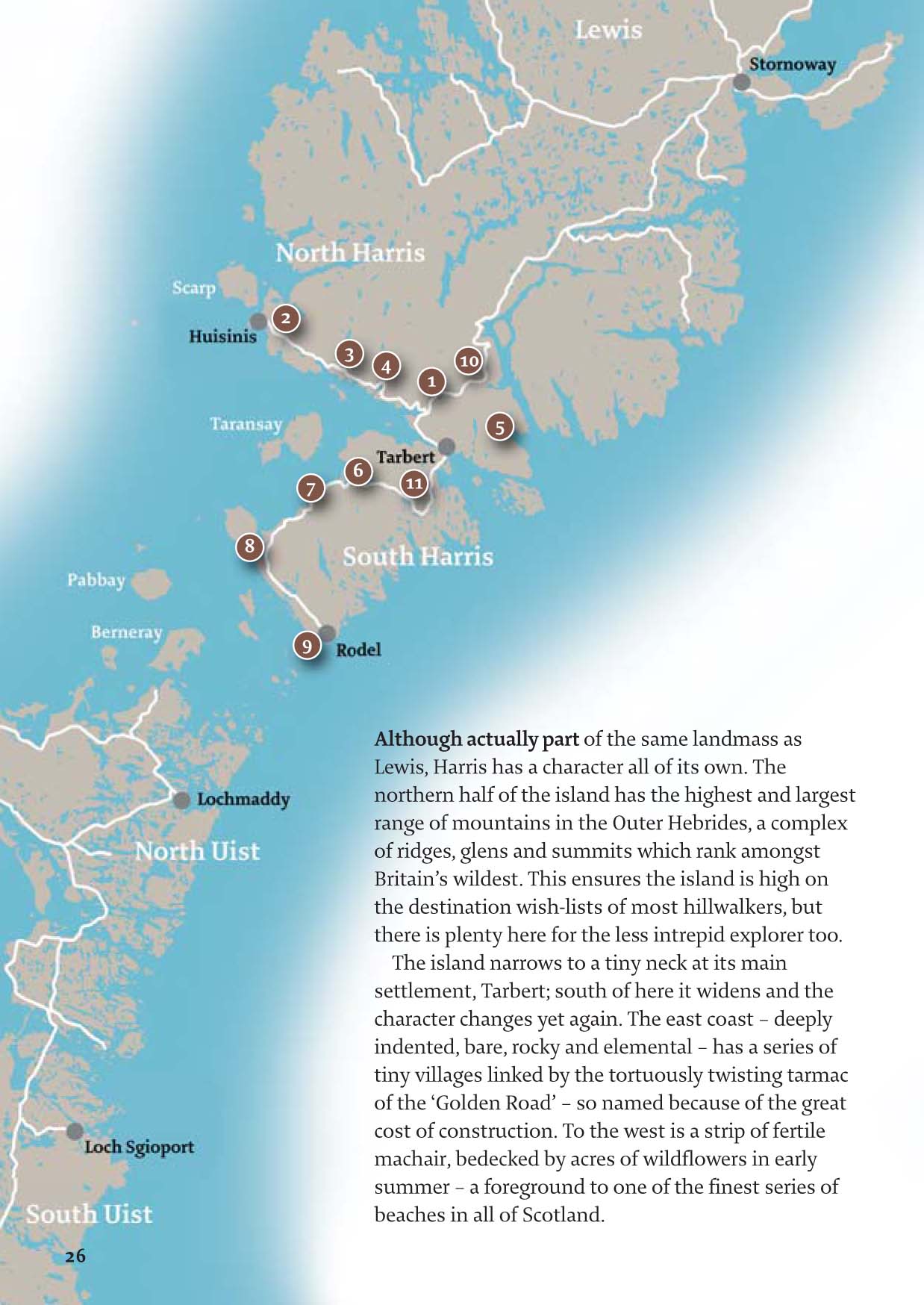

There are three car ferry routes to the Outer Hebrides, all operated by Calmac. The longest are the ferries from Oban to the more southerly islands, calling at Castlebay on Barra and Lochboisdale on South Uist. The shortest and cheapest routes are from Uig on Skye to Lochmaddy on North Uist or Tarbert on Harris, but these involve the longest drive for many people. Further north, the main town of Stornoway on Lewis is served by ferries from Ullapool. Whichever ferry route is used, be sure to book well ahead for vehicles as the boats are often full in the summer. The alternative is to fly; Flybe operates flights from Glasgow, Edinburgh and Inverness to Stornoway, whilst there are also flights from Glasgow to Benbecula and to the unique beach runway on Barra. Once on the islands, the Outer Hebrides have a surprisingly extensive network of bus routes, and many of the walks can be reached with the aid of public transport. However, the lack of buses to remoter areas and scheduling around the schoolday mean this requires careful forward planning. Further information can be found at local tourist information centres, or from Traveline Scotland.

Access, crofting land and dogs

Scotland has some of the most liberal access laws in Europe thanks to the Land Reform (Scotland) Act 2003. This gives walkers the right of access over most Scottish land away from residential buildings, but also entails responsibilities which are set out in the Scottish Outdoor Access Code. Crofting is much in evidence in the Outer Hebrides, with sheep and cattle often grazing on open land, and the land provides a rich habitat for many species of groundnesting birds. For these reasons, dogs must be kept under close control in spring and early summer and at all times when livestock is present. Even an encounter with a friendly dog can cause a pregnant ewe to abort. See the website outdooraccess-scotland.com for the best advice on responsible behaviour.

History and culture

The Outer Hebrides have a long and rich history, evinced in the ancient monuments, the most celebrated of which are the magnificent Standing Stones of Callanish. Dating back around 5000 years – older even than Stonehenge – their true purpose is unknown, though many believe they were used in rituals relating to the stars, the moon and the landscape. Also dating from the Neolithic period are chambered cairns used for burials, the finest of which features in the walk at Barpa Langass, while the Iron Age roundhouses on the Cladh Hallan walk, dating back to 1100BC, were inhabited for around 900 years. By the end of this period, the well-preserved circular broch at Dun Carloway is thought to have been built as a defensive residence and remained in use for many centuries. By the 9th century the isles had come under the control of Norse raiders and were formally ceded in 1098. Important evidence from this period includes excavations which revealed the site of a vast hall at Bornais, passed on the Rubha Aird a’Mhuile walk. The chessmen discovered in the sands at Uig on Lewis are one of the most remarkable historic finds, but the most obvious reminders of Norse rule are perhaps in many of the place names.

Over the centuries, the ownership of the isles was contested, coming under Gaelic control after the victories of Somerled – nominally the islands were now part of Scotland, but were ruled by the Lords of the Isles until 1493.

Following the Treaty of Union in 1707, the isles became part of the Kingdom of Great Britain. There were strong sympathies here, however, for the deposed Stuart family. Thus ‘Bonnie’ Prince Charles Edward Stuart landed on the shore of Eriskay in 1745 to begin his, ultimately unsuccessful, campaign to regain the crown for the Stuarts. The rebellion was utterly crushed at Culloden near Inverness in 1746, and the Prince’s subsequent flight included the romantic story of his escape from Benbecula, aided by Flora Macdonald, to Skye, made famous throughout the world by the Skye Boat Song. In the aftermath of Culloden, the Highlands and Islands were ruthlessly repressed, with tartan and written Gaelic banned. The clan system began to collapse as the chiefs turned their backs on their people and became mere landlords. What followed were the notorious Clearances in the 19th century. People were forced from the fertile machair of the west to the poor soils of the east. Many sought a new life across the Atlantic. One landlord even tried to sell the island of Barra to the government for use as a penal colony. Abandoned settlements dating from the Clearances can be seen on various isles; the lonely ruins of Stiomrabhaigh are visited on one walk.

The Crofting Act of 1886 gave crofters security of tenure, but much land was now in the hands of large landowners and so the unrest persisted. By the turn of the century, land raiders fought against landlordism, most famously on Lewis and Vatersay. The raids were partly successful and the Congested Districts Board and Deer Forest Commission saw more land eventually come back into local productive use. Today the Outer Hebrides are still largely a crofting landscape, with a culture distinct from that of the mainland: this is the chief stronghold of the Gaelic language, still spoken fluently by more than half of the population. Religion also plays a major role here. Barra and South Uist are mostly Catholic, but Presbyterianism is very strong, especially in Lewis and Harris, where the Sabbath is strictly observed and most businesses close for the day.

Natural history

One of the most characteristic habitats in the Outer Hebrides is the machair – wild flower-rich grasslands that fringe the beaches of the western seaboard and owe their fertility to the seashell content of the sand which has blown over the peat – a riot for the senses in summer and a delight for keen botanists. On the coast, otters are best sought to the east, whilst minke whales and other marine mammals may be seen in summer, and grey and common seals are fairly ubiquitous. The peaks of Harris are home to a good population of Golden eagle, which may be spied on the Eagle Observatory walk, the ascent of An Cliseam or the stalkers’ path up to Sron Uladal. In recent years, white-tailed eagles – even larger than their golden cousins – have returned, and the cliffs are home to razorbills, puffins, guillemots and shags, with both Arctic and great skua whirling overhead. The bird which best symbolises the islands, however, is the elusive corncrake – seldom seen, though its rasping call is often heard from the reeds and nettles around the machair of the west.