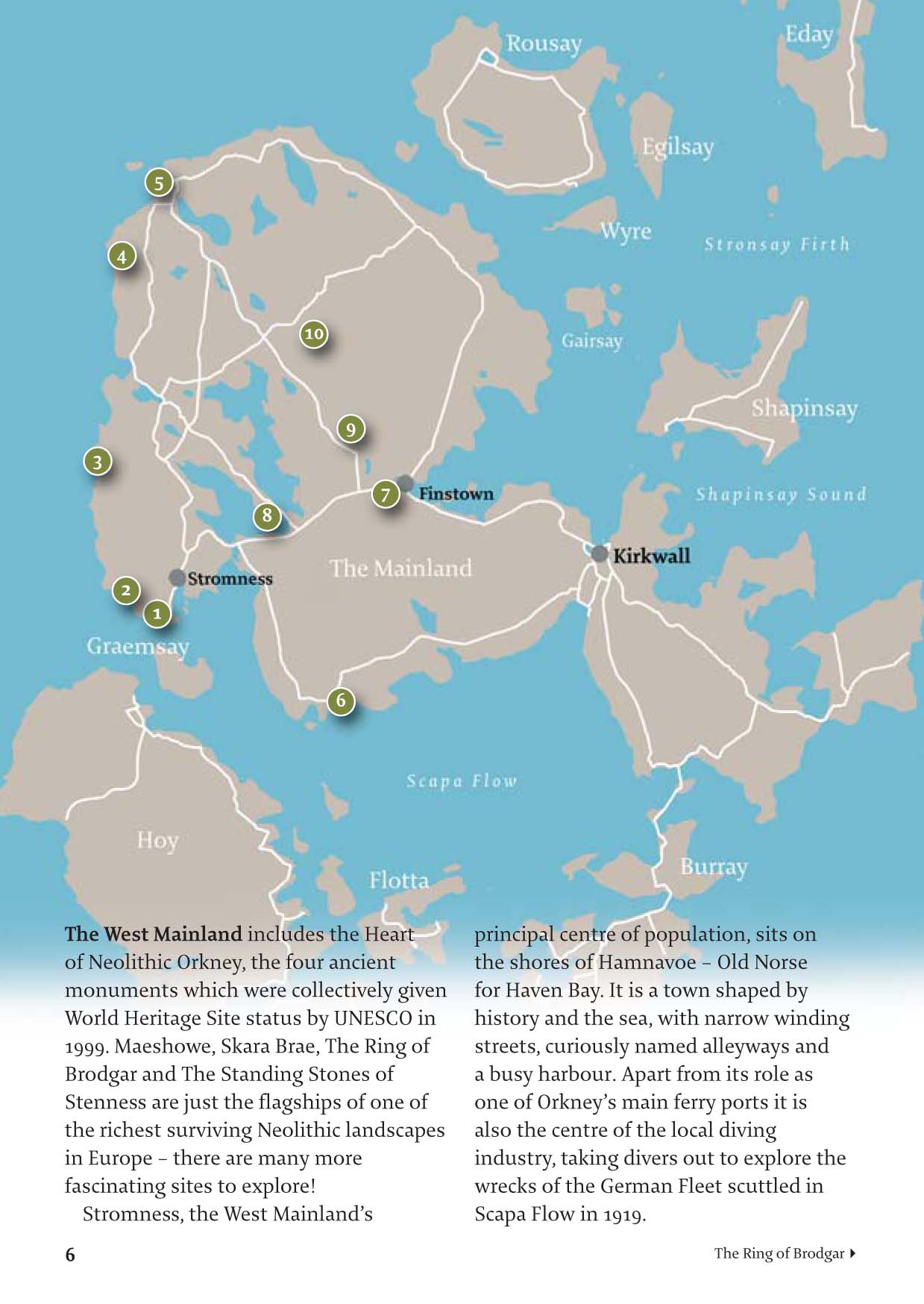

History

Orkney’s history is longer than most. Archaeologists have evidence of human activity dating back 9000 years, from soon after the last ice age. Since the first arrival of nomadic hunters, humans have left their mark. Neolithic houses, Iron Age brochs, Pictish artwork, Viking churches, and medieval castles and palaces, right through to 20th-century fortifications, history is everywhere and very tangible. Outwith the most famous sites, visitors are free to wander through, round and among standing stones, burial tombs and gun emplacements. Access is usually unsupervised, and visitors can linger and ponder as long as they like. There are superb museums in Kirkwall, Stromness and Lyness, not forgetting the farm museums at Corrigall and Kirbister, and a network of local and island heritage centres. They make an excellent job of bringing Orkney’s long story to life.

Walking in Orkney

Orkney is famous for its changeable weather and the old line about ‘four seasons in one day’ is a joke, but only just. Check the local weather forecast before you go and be prepared, regardless of the season. Good footwear is a must and it is always sensible to carry a waterproof jacket and trousers, even if the day starts off sunny. Several of the routes in this guide follow cliff edges and great care should be taken, particularly when walking with children. On some of the smaller islands it is not possible to buy food, yet the ferry times may require you to spend several hours there, so be sure to take a flask and something to eat. Elsewhere, Orkney’s rural and island shops struggle valiantly to provide a local service and it is good to support them where you can. Mobile phone reception in Orkney is surprisingly good, but do not rely on getting a signal when you need it. Always make sure someone knows where you are going and when you expect to return.

Access

Scotland’s liberal access laws, allowing the public freedom to roam the countryside regardless of whether it is privately owned or not, are enshrined in the Land Reform (Scotland) Act 2003. These rights are balanced by responsibilities to treat the land, and those who make their living from it, with respect and consideration. Leave gates as you find them, try not to climb fences, avoid walking through crops and always take your litter home.

Dogs and birdlife

There are certain times of year – during lambing, calving or the bird-nesting seasons – when a rampaging labrador can do great harm. Dogs should always be kept under proper control – and on a lead near livestock. Groundnesting birds have enough trouble coping with nature’s predators without having to contend with family pets as well. Seal pups could be abandoned if your dog separates them from their mother. Do not enter a field where there are cattle with calves at foot. It should go without saying to clean up after your pet. Sadly, many people don’t bother. Please don’t be one of them.

Orkney is brilliant for birdwatching, but there are some birds you need to watch closer than others. The great skua, aka the bonxie, is the bull-terrier of the bird world. Get too close to its nest or its young and it will not hesitate to attack to drive you away. Likewise the Arctic tern, sleek and sporty, can scare the living daylights out of anyone who strays too close to its colony in the breeding season. Generally speaking, from late April until the beginning of August it is important to avoid disruption to the nesting sites by sticking to established paths where they exist and backing off if you see signs of visibly agitated birds, alarm calling and mock (or actual!) dive bombing. If you do find yourself under attack, hold a stick or jacket above your head and clear the area as quickly as possible. To get the most from your visit, it is worth equipping yourself with a good bird book. Those produced in the islands also tend to include the local names, helping you to tell a Sula (Gannet) from a Scarf (Cormorant), and a Loon (Red-Throated Diver) from Little Footy-Arse (it’s a Grebe. Honestly!)

Travel

Buses in Orkney operate on a ‘hail and ride’ principle, meaning you can ask the driver to pick you up or drop you off wherever you want – as long as it is on the route.

A number of the North and South Isles have local buses which meet ferries, although several only run a part-time service and must be pre-booked. Check ferry times carefully as some routes must be booked in advance and some crossings are ‘on request’. That means the ferry might not sail if you have not told them you will be waiting. Flights to the North Isles of Orkney run frequently, but seats are in great demand. Book as far in advance as possible for the best chance of a ticket. The tourist information centre in Kirkwall should be able to provide timetables and booking information.

About this guide

The 40 walks in this guide range from a short stroll to hikes of several hours, but most can be completed in half a day or less. The majority are circular, several are lollipop-shaped and some require you to return by the same route. They all, however, end up back where they started, so you will not find yourself miles from your car. Each route is prefaced by an indication of the distance involved and the time it is likely to take. The latter is estimated on the time it took the author to walk the route (averaging around 3.5km per hour) before adding a little for tea, toilet and tourism stops. The timings should be regarded as a rough guide, and if you have to catch a bus or boat at the end of the walk, leave plenty of extra time! Only on a couple of routes will you be asked to set off across the heather without a path to follow, and

never without your immediate destination being in view in clear visibility. That said, walking in Orkney should not be underestimated and good visibility cannot be relied upon. The sketch maps are to help in planning your trip and are not sufficiently detailed to navigate by. It is advisable to carry the relevant Ordnance Survey map. Any compass directions are approximate, and lefts and rights are relative to the direction of travel. Where a walk involves crossing to a tidal island, it will be mentioned in the notes. Always ensure you get reliable advice on the state of the tides before crossing. If you get it wrong, you could have a cold, wet and lonely few hours before getting back across.

Pronunciation advice

Visitors will be met throughout Orkney with goodwill, but you can earn extra Brownie points by avoiding some common mistakes. 1. Orkney should never be referred to as ‘The Orkneys’. It is Orkney or, if you want to be very formal, The Orkney Islands. 2. The biggest island in Orkney is called ‘the Mainland’, not ‘Mainland’. It requires the definite article at all times. 3. Islands and parishes ending in ‘ay’ – that is most of them – have no emphasis on the final syllable (e.g. Westray rhymes with ‘vestry’, Sanday with ‘brandy’ and Harray with ‘marry’). North Ronaldsay, Rousay, Birsay etc all follow the same rule. The same applies to most place names: Stromness, Deerness and Tankerness are pronounced like ‘fondness’ with the ‘ness’ being almost dropped. Among the exceptions is Finstown which prefers equal emphasis across both syllables. Likewise, Orphir is simply ‘Or-fur’, and never ‘Or-fear’. Particular places mentioned in this guide which require careful pronunciation include Egilsay (AY-gillsy), Noltland (NOWT-lan), Brodgar (BROD-yer), Brough should rhyme with ‘loch’, Quoy sounds like the ‘River Kwai’ (e.g. Kwai-loo), Doun Helzie is pronounced ‘Doon Helly’ and Wideford is ‘WIDE-fud’, never ‘Widdy-ford’. The parish of Holm is pronounced ‘ham’. Islands with holm in their name (e.g. Lamb Holm) are pronounced ‘home’, and Rothiesholm in Stronsay is pronounced ‘Rouse-um’. ‘Best kens’ as an Orcadian might say – roughly translated as ‘Go figure!’